In this post

We have seen how extraneous variables can occur and how they affect the outcome when carrying out research and so it is important for psychologists to know how to try and control these, and they do this by various methods, which include:

- Standardised procedures

- Counterbalancing

- Randomisation

- Single blind techniques

- Double blind techniques.

Standardised procedures

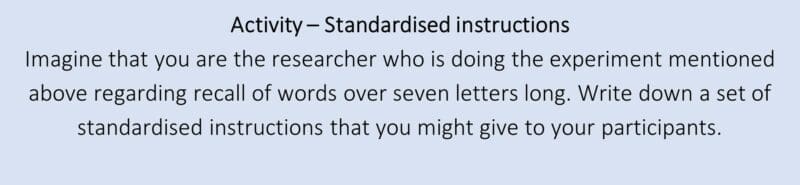

As its name suggests, when procedures are standardised, they are kept the same for all participants so that the research is carried out fairly and to try to ensure better reliability for the results. This applies, for example, to the instructions that are given to the participants prior to the research taking place – the researcher should read the instructions to the participants or they should read them themselves. The important thing is that all participants get the same instructions. This way, the instructions do not become a potential confounding variable that might have an effect on the outcome of the experiment.

Similarly, when the data from the experiment is collected, it is vital to ensure that this is also standardised, which is not as easy as it sounds. One example of this might be that a researcher was testing memory and wanted to know how many words of over seven letters long the participants could recall after a one-minute delay. It is important that all participants get the same words so that the data which is collected is standardised, i.e. it has been collected (via the identical words for each participant) in exactly the same way.

Generally speaking, researchers can try to ensure that the standardised procedures take place by ensuring all participants:

- Undergo the research in the same location

- Have the same equipment or materials

- Are exposed to the same environment, such as the same lighting, temperature or noise levels

- Undergo the research at the same time – people can react very differently at different times of day

- Are given the exact same instructions in the exact same way.

Standardised procedures are useful as they enable the researcher to have full control over any potentially extraneous variables. However, this does mean that the experiment may lack ecological validity, as it will not truly reflect a real-life situation.

Counterbalancing

Sometimes, when a repeated measures experiment takes place, participants may perform better when they undertake the task for a second time because they know what they are doing or they may perform worse, because they are tired. These are known as order effects.

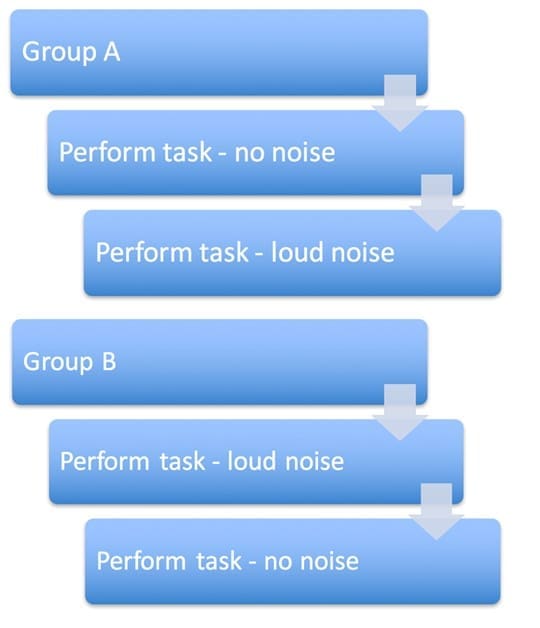

These effects can be overcome by counterbalancing, which is a technique where the researcher alternates the order in which participants perform in different conditions of the experiment.

For example, if someone wanted to find out if participants were affected by noise when they were asked to complete a physical task such as the one below, they may need to counterbalance. The participants in the sample would split into two groups: A and B. The counterbalancing may then be carried out like this

Both groups would carry out the experiment at the same time but this can be tricky to undertake and the researcher may find that it brings about other types of potentially extraneous variable.

Randomisation

Randomisation is a bit like ‘shuffling’ the participants so that they take part in the experiment in no particular order. It provides an alternative to counterbalancing when trying to deal with order effects.

When randomisation is applied, this means that the order of presentation of experimental conditions (such as loud noise or no noise in the previous examples) is adapted by a random strategy such as tossing a coin or drawing names from a hat.

This technique is not perfect because although it is random, there is still a chance that the order in which the participants take part will affect the outcome, as there may still be chance differences in the numbers of participants who experience the condition in a particular order.

Single blind techniques

When a single blind experiment is carried out, the participants do not know if they are a part of the experimental group or the control group – let’s remind ourselves what these are:

- Experimental group: is exposed to the independent variable

- Control group: is not exposed to the independent variable.

The researchers, however, do know which group the participants have been allocated to.

This method is thought to eliminate the possibility of participants ‘acting’ in a way that they think they should. For example, if a participant thought that they were in an environment that made them sleepy and so their recall in a memory test was affected, they may ‘act’ in a sleepy way because this is what they think will be expected of them, as they are in the sleepy environment. This is sometimes referred to as the ‘placebo effect’.

Double blind techniques

As you may have guessed from the definition of single blind techniques, a double blind technique is where neither the researcher nor the participants know which group they have been allocated to.

This is thought to eliminate any kind of bias from the researcher when analysing the results, as well as from the participants when they are taking part.

This is because, as the participants do not know which group they are in, their beliefs about the research they are taking part in are less likely to influence the outcome. Secondly, since researchers are unaware of which participants are in the experimental group, they are less likely to reveal accidentally subtle clues that might influence the outcome of the research or how the data is collected at the end.