In this post

Fiction refers to texts that are imaginary (made up). The main purpose of all fictional texts is to entertain. Types of fictional texts include forms of prose, poetry and drama.

Prose

- Novels

- Novellas

- Short stories

Novels refer to stories that normally have several characters in them, several points of action and are usually divided into chapters. Novels tend to follow a literary tool known as a narrative arc. A narrative arc refers to the construction of a plot in a novel. Normally, this plot is chronological (events told in the order in which they occurred) but it does not always have to be – we will discuss a narrative arc further in the last unit of this course.

Novellas are shorter in length than a novel but longer than short stories. Like novels, novellas tend to follow the structure of a narrative arc and can include several characters (although normally fewer than a novel).

Short stories are shorter than novellas. Short stories are the most likely form of prose that you will come across in the exam. They still tend to follow the structure of a narrative arc but have fewer characters and less points of action; they are much simpler than the larger forms of prose.

Poetry

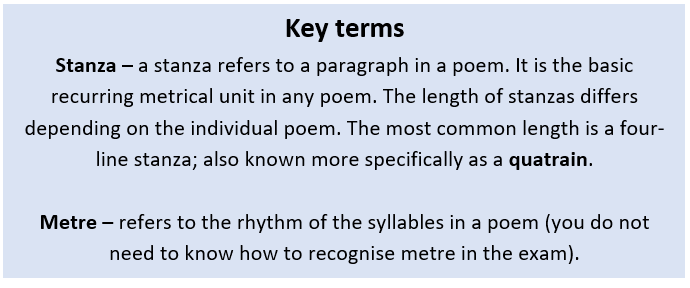

Poetry is a form of fiction that has a distinctive style and rhythm. It is the expression of feelings and ideas that are intensified by the style, rhythm and literary devices in the writing.

Drama

Drama refers to plays. A play can be for either the theatre, radio or television. A play can follow the structure of a narrative arc but it does depend on the genre of the play; for example, the genre ‘theatre of the absurd’ does not tend to follow the traditional structure of a plot and can be a lot more complex.

Setting

The setting of a fictional text is the place and time that the characters and actions are set in. Settings can be real (for example, in a real town in England, or a country in the world such as Africa) or they can be fictional (for example, texts may be science fiction and be based in outer space on an unknown planet); alternatively, they could be less specific and set in a type of place or event (for example, a school or birthday party etc.).

Setting is an important aspect of any fictional text (and some non-fiction texts also). The time of day, year or season can have crucial effects on how the story is told and how effectively it works; for example, a horror story would work better at night-time, possibly in a more isolated setting such as a forest.

The historical context of a setting can also have significant effects on the plot and ideas surrounding it. For example, in Jane Austen’s novel Pride and Prejudice, which is set in the early 19th century, marriage is one of the central subjects and problems presented. This is established from the first line: ‘It is a truth universally acknowledged, that a single man in possession of a good fortune must be in want of a wife’ but it is also established in the historical context. During this time, many men in England were sent off to war, especially many men in the middle and higher classes of society. This meant that eligible men were scarce to middle and higher class women looking to marry. This historical context adds to the subject of marriage in the novel.

An example of the description of a setting can be seen in the first five stanzas of Thomas Gray’s poem Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard (1751):

| The curfew tolls the knell of parting day, 1The lowing herd wind slowly o’er the lea,The plowman homeward plods his weary way,And leaves the world to darkness and to me.Now fades the glimm’ring landscape on the sight, 5And all the air a solemn stillness holds,Save where the beetle wheels his droning flight,And drowsy tinklings lull the distant folds; Save that from yonder ivy-mantled tow’rThe moping owl does to the moon complain 10Of such, as wand’ring near her secret bow’s,Molest her ancient solitary reign. Beneath those rugged elms, that yew-tree’s shade,Where heaves the turf in many a mould’ring heap,Each in his narrow cell for ever laid, 15The rude forefathers of the hamlet sleep. The breezy call of incense-breathing Morn,The swallow twitt’ring from the straw-built shed,The cock’s shrill clarion, or the echoing horn,No more shall rouse them from their lowly bed. 20 |

There are many features we could comment on in Gray’s poem, however, at the moment we are going to focus on just the setting he describes.

Analysis

The setting of the poem is mentioned in the title: ‘a Country Churchyard’. The speaker is at the churchyard when ‘curfew tolls the knell of parting day’ (line 1) and we know that a churchyard is surrounded by gravestones. A parallel is placed between the ‘parting day’ and the spirits in the graves that are thought to part and pass on to the afterlife. Although it sounds eerie in the first couple of lines, the poem is not about ghosts but how the living remembers the dead. In later stanzas of the poem, the speaker goes on to imagine the lives of the people in the graveyard – in their country cottages or ploughing the fields. The parallel presented between the time of day and the spirits opens the main subject of the poem: the dead.

The setting continues to be described; ‘Now fades the glimm’ring landscape on the sight,//And all the air a solemn stillness holds,’ (lines 5-6) which establishes that it is the evening and it is dark; ‘the moping owl does to the moon complain’ (line 10). Even though the poem is set in a churchyard, surrounded by graves and darkness, the setting is imagined as peaceful, rather than something that would often feel eerie. The peaceful atmosphere of the setting is reinforced by the strict metre and rhyme scheme of the poem.

There are more features of the setting that we could mention here; for example, you could say that the figures of speech that are frequently used reinforce the peaceful atmosphere that Gray is attempting to create.

Themes

Texts do not just consist of the actions and events that take place but also consist of ideas that run throughout. These ideas are known as themes. Some of the most common themes that you may find in texts are:

- Ambition

- Betrayal

- Death

- Duality of man

- Heroism

- Fate vs free will

- Friendship

- Guilt

- Love

- Money

- Power

- Revenge

- Transformation of men

- Violence

For example, in Shakespeare’s Macbeth, Macbeth and Lady Macbeth plot to murder King Duncan so that they can become King and Queen – the main theme of the play is therefore the two characters’ overriding ambition which results in the death of the King and eventually their own downfall.

Narrative Voice

The narrative voice of a piece of fiction refers to how the story is told. In some cases, the narrator of a text will also be a character in the story and will be speaking in first person; however, in others the narrator may not be a character in the story and will be speaking in third person (there is also such a thing as a second person narrator but we do not need to go into detail about this yet as it is a very rare form of fictional narration).

You can easily recognise if a text is told in the first or the third person. If told in the first person then the pronoun ‘I’ will be seen throughout, but if told in the third person then the pronouns ‘he’, ‘she’, ‘it’ and ‘they’ will be seen (except in the character’s speech and dialogue when characters will always be speaking in third person).

A text that is written in first person narration indicates a clear point of view – the point of view of the character narrating. A third person narrator, however, has more freedom than a first person narrator. A third person narrator can either closely follow one character (known as a third person limited narrator) or it can follow a few characters and take an omniscient standpoint (known as a third person omniscient narrator).

Third person omniscient narrators do not tend to be biased in their point of view as they tend to remain neutral towards characters, ideas and events that occur in the narrative. However, first person narrators and third person limited narrators tend to have a specific point of view and present certain feelings or attitudes throughout the narrative. This can affect the way a reader perceives the events and characters that are being presented to them through the narrator. For example, in Edgar Allan Poe’s The Tell Tale Heart, the narrator has such a strict point of view that he appears as an unreliable narrator to the reader; this creates the drama and tension that this short story is so praised for.

An example of a novel told using first person narration is the opening paragraph of Jonathan Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels (1726):

| My father had a small estate in Nottinghamshire: I was the third of five sons. He sent me to Emanuel College in Cambridge at fourteen years old, where I resided three years, and applied myself close to my studies; but the charge of maintaining me, although I had a very scanty allowance, being too great for a narrow fortune, I was bound apprentice to Mr. James Bates, an eminent surgeon in London, with whom I continued four years. My father now and then sending me small sums of money, I laid them out in learning navigation, and other parts of the mathematics, useful to those who intend to travel, as I always believed it would be, some time or other, my fortune to do. When I left Mr. Bates, I went down to my father: where, by the assistance of him and my uncle John, and some other relations, I got forty pounds, and a promise of thirty pounds a year to maintain me at Leyden: there I studied physics two years and seven months, knowing it would be useful in long voyages. |

An example of a novel told using third person narration is the opening of Virginia Woolf’s Mrs. Dalloway (1925):

| Mrs. Dalloway said she would buy the flowers herself.For Lucy had her work cut out for her. The doors would be taken off their hinges; Rumpelmayer’s men were coming. And then, thought Clarissa Dalloway, what a morning – fresh as if issued to children on a beach.What a lark! What a plunge! For so it had always seemed to her, when, with a little squeak of the hinges, which she could hear now, she had burst open the French windows and plunged at Bourton into the open air. How fresh, how calm, stiller than this of course, the air was in the early morning; like the flap of a wave; the kiss of a wave; chill and sharp and yet (for a girl of eighteen as she then was) solemn, feeling as she did, standing there at the open window, that something awful was about to happen; looking at the flowers, at the trees with the smoke winding off them and the rooks rising, falling; standing and looking until Peter Walsh said, “Musing among the vegetable?” – was that it? – “I prefer men to cauliflowers” – was that it? He must have said it at breakfast one morning when she had gone out on to the terrace – Peter Walsh. He would be back from India one of these days, June or July, she forgot which, for his letters were awfully dull; it was his sayings one remembered; his eyes, his pocket-knife, his smile, his grumpiness and, when millions of things had utterly vanished – how strange it was! – a few sayings like this about cabbages. |

When analysing narrative voice, you should try and answer the following questions:

- Does the text have a narrator?

- Is the narrative told in first, second or third person?

- Who is it that is speaking? Are they a character in the narrative?

- What do you learn about them throughout the narrative?