In this post

In order to be able to interact with our physical environment, we need to be able to make sense of what we see, and this is something that most people can do automatically.

Anything which we have seen before we instantly recognise, and even in cases where we are unsure about what something is, we will usually find a way of reaching a conclusion about what we are seeing.

The ability to make sense of the environment, or to perceive things, begins at a very early age and even very young children are able to recognise familiar shapes, colours and even work out how to use depth cues, which is a term that we will look at in more detail shortly.

It is argued that perception is based on two major factors, which are:

- Visual cues

- Visual constancies

By using these, the brain is able to make sense of what the eyes are seeing and the way in which this is done is extremely complex. The process begins with our senses, which are smell, taste, touch, sight and hearing. When information is picked up by the visual sense of sight, the information received by the retinas in the eyes is sorted out and sent across into the brain where the visual cortex makes sense of what is being seen and enables the person to achieve correct perception.

Visual cues

There are several ways in which people are able to more accurately perceive their environment and these are known as visual cues. They enable someone to have the correct depth perception, which refers to how our brain is able to add a third dimension to images so that it is given depth and is not two-dimensional, which is how it is initially seen by the eye.

Some of these cues are monocular, which means that they are available to each eye independently, or they can be binocular, which means that they depend on the use of both eyes to be correctly interpreted.

Research has indicated that there are several visual depth cues which are used by the brain, the following of which are monocular:

- Superimposition

- Relative size

- Linear perspective

- Texture gradient

- Height in the plane

One important visual cue, which is binocular, is:

- Stereopsis

Superimposition

When something is superimposed, this simply means that one thing has been placed across another and so a part of the image is blocked. As you can see from the example below, it is usually perceived that the circle is closer to us than the square, followed by the triangle, which is perceived to be furthest away.

Relative size

An object which is closer will make a bigger impact on the eye’s retina than one that is further away. Therefore, if an object is perceived as bigger, then the person will know that it is closer than one that is smaller, as this one will be further away. This helps people to accurately interpret distance.

For example, if you stand at the front of a queue waiting to go into a concert, you know that the people at the back of the queue are not actually smaller than a normal sized adult, they just appear to be because they are further away than the people who are right next to you, who appear to you at normal size.

Linear perspective

A very good example of linear perspective are parallel lines. When they go off into the distance, they appear to merge together, when, in fact, they remain the exact same distance apart the whole time. (See the image of train tracks here.) This enables someone to work out the distance of the length that the parallel lines cover.

Texture gradient

Most objects and surfaces will have some form of texture. Being able to judge texture gradient enables someone to accurately perceive how near or far away something is because when it gets further away, its texture appears to become smoother, even though it has not changed. For example, when you look at a garden from a distance, it just looks like an area of green, but when you look more closely you are able to see each blade of grass individually.

Height in the plane

In someone’s field of vision, things that are at the bottom of the field are closer than things at the top, which is another way in which people are able to work out nearness and distance.

Stereopsis

The only commonly used binocular cue, stereopsis, as the term ‘stereo’ suggests, means that the two separate images perceived by each eye are brought together to enable someone to perceive something more accurately. Stereopsis is the way in which the two-dimensional images seen by the retina have a third dimension added to them by the brain.

Visual illusions

A person’s ability to perceive something accurately is not always correct, and when this happens it is referred to as a visual illusion because what is actually being seen and what the brain thinks is being seen do not match.

There are three types of visual illusion which have been identified:

- Fictions

- Ambiguous figures

- Distortions

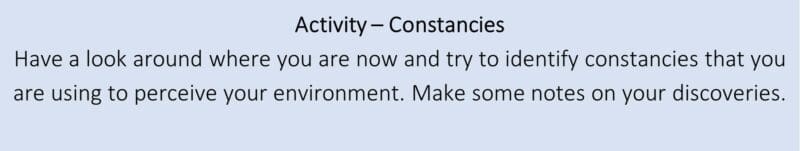

Fictions occur when someone sees something in an image that is not really there. A well-known example of this is the Kaniza triangle (pictured here).

There is not actually a white triangle in the middle of the picture but because of the arrangement of the other shapes, it does appear that there is one. This is a visual illusion.

In the image below, there appears to be a cube in the middle of the image but, again, this is not really there; it just appears to be because of the arrangement of the other shapes:

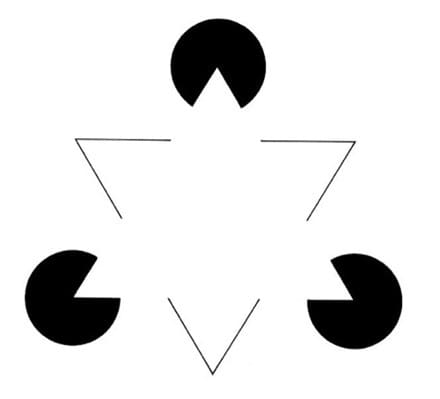

Ambiguous figures are images that can be seen in more than one way. The Necker cube is a good example of an ambiguous figure because if you look at the letter ‘o’ in the cube, sometimes it appears to be at the back of the cube and sometimes at the front:

The image below can be perceived as either a duck or a rabbit, which is another good example of an ambiguous figure – it is unclear what the image is because it could be two things

With distortion illusions, size, length and curvature are perceived as different to how they actually are. A famous example of this is the Muller-Lyer illusion, which is nothing more complex than a set of arrows. However, because the ends of the arrows are different, this leads people to believe that the mid-length of them is either shorter or longer when, in fact, they are exactly the same.

As the middle line has arrow-heads pointing outwards, this leads people to believe that this is actually longer than the other two, when, as the vertical lines at each side show, this is not the case.

Illusions help us to realise that sensation and perception are actually two separate processes because we are perceiving things that we have not sensed – i.e. seeing a triangle in the Kaniza triangle and believing that one line is longer than the other in the Muller-Lyer illusion.

Visual constancies

When an illusion occurs, it is thought that a person’s ability to use a visual constancy has failed and this is why they see something that is not there or perceive something that is not an accurate representation of what they are actually seeing.

Visual constancies enable people to see things as remaining the same even though they may actually be constantly changing.

Shape constancies enable us to work out what something is, even though we may be seeing it from various different angles or in different forms. For example, if we see a door open and a door closed, we are still able to correctly perceive this as a door even though it looks completely different in both of those states and when it is being opened or closed and is actually moving.

Colour constancies help us to see the same colour even though it may be presented to the eye in different lights. For example, in a darkened car park, you will almost certainly still be able to pick out your own car, even if its colour looks completely different to when you parked it up in daylight a few hours before.

This is another good example to show how sensation and perception are different – even though the colour of the car may appear different to our sense of vision, our perception of it remains unchanged.

Size constancies refer to how people’s perception of an object does not change even though its size may appear different – such as seeing a person from a distance rather than close up. We know that they are the same size as an average adult even though they are far away. We know that a football is not the same size as a golf ball when we see it in the distance and we also know that a house has not shrunk, just because we are seeing it from afar.